Property Marketing Balls Pt.3

Recently a sign went up on the plot of land this journal has often referred to as its «favourite inner-city prairie», advertisiting the pending erection of the Fellini Residences. That was not all: some weeks earlier this correspondent happened to pass a nearby plot of land one evening, and caught sight of the grand opening party of the show apartments, complete with marquee, red carpets and champagne butlers.

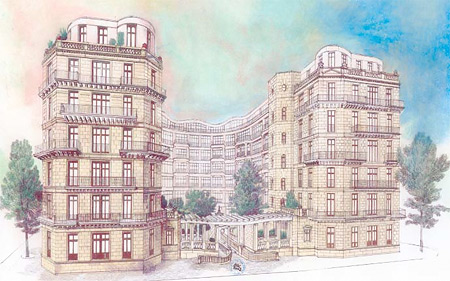

The Fellini Residences

Compared to the Choriner Höfe, the marketing of the Fellini Residences represents a more coherent attempt to integrate a building-style which takes its cues from local historical architectural movements, with the kind of prophetic lifestyle engineering we’ve seen before. However, where the new development is obviously not historical (because it is contemporary), but historicized, (because it mimicks the local architecture of the late 1700s) the marketing machinery is required to function as a kind of verbal putty, filling the intellectual gaps unavoidably left open by architectural mimicry.

And so we read on the Residence’s website:

Welcome to the “Italian quarter of Berlin!” All the inhabitants have just one thing in common: they love life and have used perhaps the last opportunity to acquire an apartment in the direct proximity of the Gendarmenmarkt (7 minutes by foot) ” Whoever lives here does not have to do without anything. The subway stations Hausvogteiplatz and Spittelmarkt are a few minutes away.

Three things are happening here. The first is that Berlin has no Italian quarter. A quick search for «Italian quarter» at Berlin’s official website berlin.de returns zero results. A similar search at Lonely Planet turns up results for San Francisco and Dublin, but not Berlin. So having established that Berlin, in all probability, has no Italian quarter, it can be safely assumed that the Fellini Residence’s image makers have just invented it. And further more, the Fellini Residences aren’t in the Italian quarter, they are the Italian quarter. Quite a claim for a single building.

La Dolce Vita. Soon in Berlin.

The second thing going on in the quote above, is the fashioning of a strong affiliation with the Gendarmenmarkt. The Gendarmenmarkt is a square in central Berlin where the Konzerthaus stands, as well as the German and French cathedrals. A statue of Schiller also stands here. The Konzerthaus was built in 1821 by Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who was German. The French cathedral was built by the Hugenots – who were French – between 1701 and 1705. The German cathedral was designed by Martin Grünberg – another German – and built by Giovanni Simonetti, who was Swiss, but probably completed his stone masonry apprenticeship in Italy.

Gendarmenmarkt: Italian flair, apparently. Not German flair.

This is not to say, however, that German architecture of the 19th Century wasn’t influenced by Italy, because it was. But the tenuous association the Fellini Residences are making between themselves and the Italian influence on the buildings of Gendarmenmarkt is laughable. Separate the Italian from the Gendarmenmarkt and the picture becomes clearer: the Italian connection being made here is a simple, romanticised northern European notion of Italian flair, temperament and lifestyle, which the Fellini Residences hope to evoke through name alone. The Gendarmenmarkt connection, meanwhile, has nothing to do with the history of architecture, but has everything to do with the fact that the square is surrounded by some of the most luxurious shopping possibilities the world has to offer. Indeed, elsewhere, the Fellini Residence website gets right to business:

Want to go shopping? How about Gucci, Moschino or Cerutti. You could also pay a visit to Ferrari and Bugatti. Or you could dine exquisitely at Bocca di Bacco, at Borchardt or at Sale e Tabacchi.

The third thing going on in the above quote is the deliberate glamorisation of location through an extremely selective information policy. The cliché goes that property is about three things: location, location, and location. But even here the Fellini Residences are on shaky ground, despite what they claim. The map and key below attempt to explain why:

1. The Fellini Residences

2. Gendarmenmarkt

3. Hausvogteiplatz and underground station

4. Spittelmarkt and underground station

5. Moritzplatz and underground station

What the map above reveals is that whilst the Fellini Residences (1) are happy to associate themselves with the glamour of Gendarmenmarkt (2) and the practicality of Hausvogteiplatz underground station (3), they are situated just as close to Moritzplatz (5) in neighboring Kreuzberg, which is decidedly lacking in flair having never really recovered from allied bombing during WWII.

Moritzplatz: German flair, apparently. Not Italian flair. [Photo: Herr Popp]

The skewed lens through which the developers are keen for prospective customers to gaze through is almost endearingly whimsical. Whilst not quite as abrasively cretinous as the manure pile devised by the Choriner Höfe, there is still a danager at the center of all this spin. It is the danger of isolation.

In all its cockeyed preoccupation with itself, the Fellini Residences are currently, in their unbuilt form, only happy to engage with the parts of Berlin it already sees reflected in itself. It has little time for anything which doesn’t fit into this scheme of things. How else then to explain the complete lack of interest it shows in anything just footsteps away: the Berlin wall for example, which ran not five meters from the antique fountain planned for the center of the Residence’s «jewel garden» is not mentioned once. And when one considers the 171 people who were killed or died trying to cross the wall the following words are particularly distasteful:

You do not have to die to arrive in paradise. You have it right on your doorstep.

Despite its historic ambitions, real history is an insignificance compared with the heavenly delights on offer within the compound. And lost on the Fellini Residences too is any sense of historic irony, a sense of transience and incongruity, which could have instilled the development with a modicum of genuine dignity beyond its fetishisation of form and material.