Une manifeste nicoise

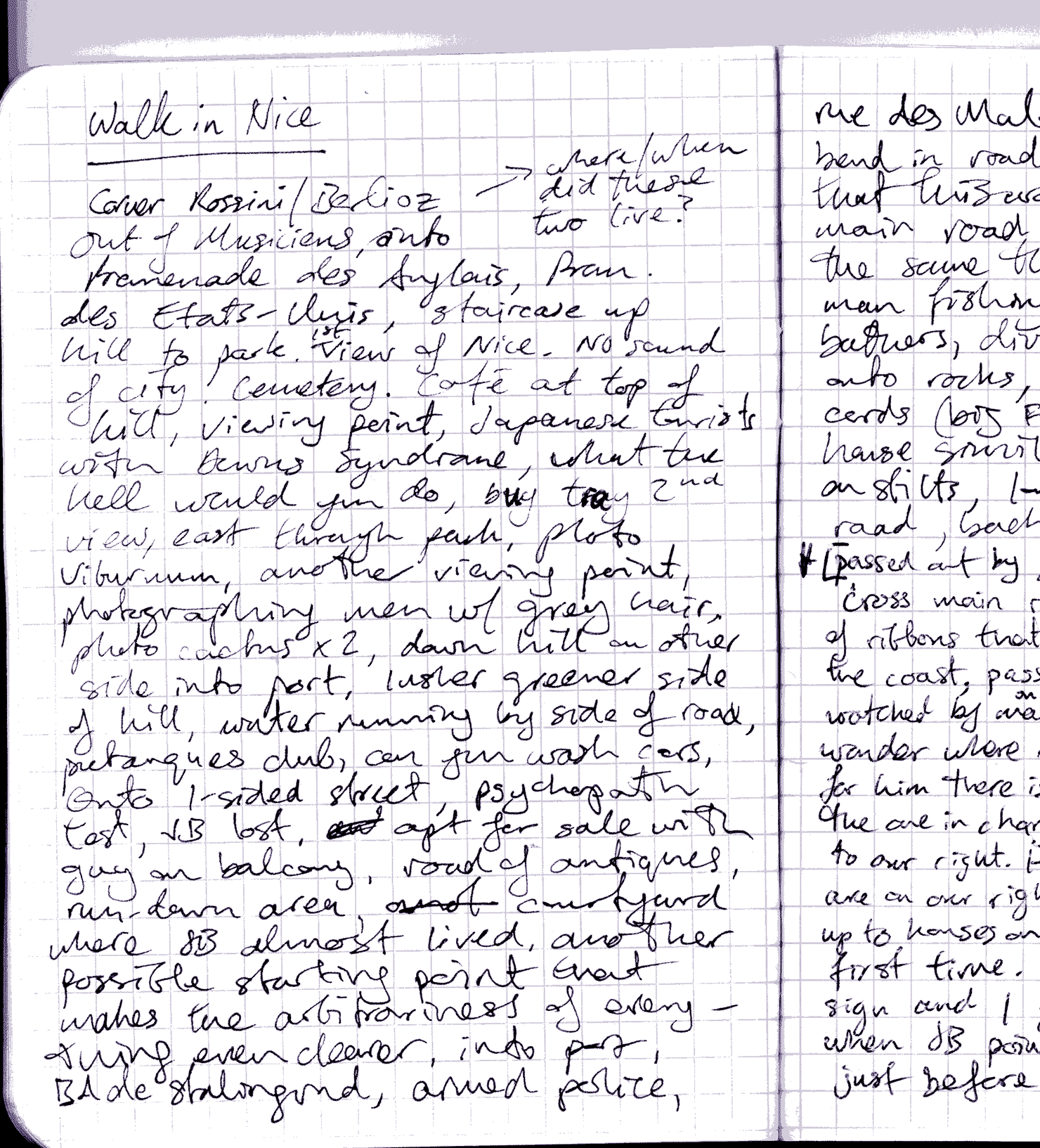

We set out from the apartment quite late in the day, after a morning of eating and listening to the radio. Turning left out of the main door, out of Rue Rossini and onto Rue Berlioz, we made for the sea, leaving the Musiciens neighbourhood. It takes five minutes to reach the landmark of the Hotel Negresco, which stands prominently on the Promenade des Anglais.

This will take some time to get through. You are reading a record of the walk that I took with Tom while visiting him in Nice in the south of France at the end of June 2004. The start is when we left the apartment and the end will be when we returned.

The previous night I had started reading a book about the walk as an architectural/cultural activity. It described how the Paris Dadaists went on a city walk, whose purpose and route were deliberately unclear. They photographed themselves at the meeting point, beside a modest church in some Paris neighbourhood. It was the first time that I really understood Dada; through absurdity to reveal the true nature of things. Is something as banal as walking worth recording, worth commenting on? Is a walk an event? These people took what I suppose they would have called a promenade, or at least went through the motions of it, and raised for me the question of why one does such a thing as take a walk. And when one does, why is it sometimes important to have a route and other times not? And why does it seem important to record the event sometimes and other times not?

The Promenade des Anglais is a busy place, especially so on the weekend. It is hemmed in on the landward side by a dual carriageway that is constantly streaming with traffic. On the other side is the sea, several metres below. The beach itself is not really the main attraction in Nice. It is narrow and stony. The sea bed drops sharply away and the waves crash down on your head and the large stones hurt your feet. It is difficult to bathe gracefully there. So those who are on the beach are just lying about, some on the loungers arranged in rows and corralled by little fences that belong to the small bars that huddle against the retaining wall of the promenade. So the thing to do on the promenade is to walk and to watch other people doing the same thing. Some rollerblade, some jog, some cycle, but most walk. We walked east, a little quicker than most. It would be absurd to take a walk along the coast in Nice without going along this custom-built stretch, so we did what seemed logical and walked.

On our left was the beginning of the strip of green that marks where the now diverted river used to run. After that, the promenade is called Quai des Etats Unis. There is an interesting reason behind these French-foreign names for this French-foreign place, and I read about it somewhere at the time. If I had sat down to write this within a few days of the walk itself, I would remember, but I did not and I do not. In fact, many of the details have already started to fade. But that may be no bad thing. This account may not be entirely accurate, but it will probably be faithful.

Most of the ground we covered that day was along the coast and this is an attempt among other things to give the measure of this famous coastline. I can sum things up by saying simply that we walked south to the beach, then east along the sea over the first headland and then on to the next headland, which we ascended and then turned inland, reaching the outskirts of the city, where we took a bus that took us back into the city centre. That is the short of it, and I could leave it at that. But I want to give the long of it.

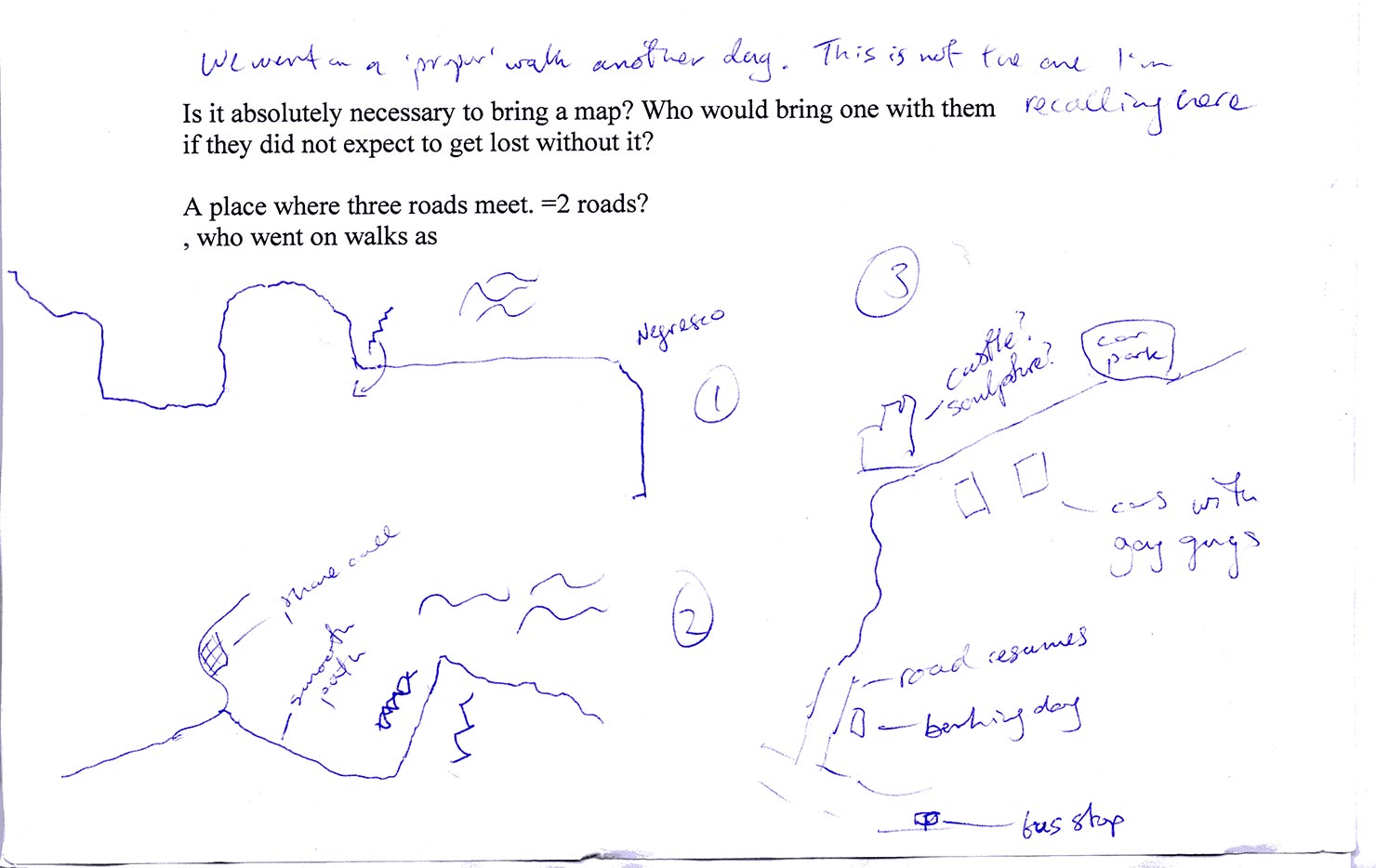

Tracing maps for geography class in school: the problem was how accurately to follow the outline of the coast of Ireland. Sometimes you would be faithful to every in and out of peninsulas of Cork and Kerry, other times you would round them off a little, gliding past little harbours and bays. Measured in miles or kilometres, the difference can be a factor of between 1.5 on smooth coasts and 3 on rough ones. In fact, a coastline can be infinitely long if you want it to be. I have barely begun this little piece of writing and the end is inching away from me, new ideas always intervening and demanding careful tracing. Come to think of it, the start is also racing away from me as I see gaps that need filling. This makes the sentence before last already an artefact of the process of writing, seeing as it may no longer be 754 words in when I am finished with this. This could go on forever. It may be time to let a few details go. Or maybe I’ll put in a better map at the end.

The Quai des Etats Unis turns around the headland at the end of the vista. Tom wanted to show me the headland itself. We climbed a long staircase in the side of the rock, strangely close to the balconies of the very last building along the seafront. A brave jump would land you onto one of them. These were the first of many balconies that would strike me during the day. We emerged into a park which we followed inland a little. There was a cemetery there, which one guidebook said is the fourth biggest in Europe, but I’d like to know what scale they were using to measure it, because to me it seemed a very average-sized affair.

Then we reached the first viewing point of the day. We stood at a chest-high wall and looked downwards and west at the old city beneath us and the rest of the city beyond. On the right the buildings sloped up to the mountains that squeeze Nice and the rest of the towns on this coast into a narrow strip. I was surprised that we could hear so little noise from the city. In the distance was a mountain with a square silhouette that Tom described climbing up once. Looking at the picture I took from there, I think I am looking at an Italian centro storico. I did not take a picture of the larger view. My description of it will have to be taken on faith.

The camera I used was Tom’s little digital one. He gave it to me for the whole day and encouraged me to wear the case for it on my belt. I acquiesced.

We turned back into the park, discussing whether [the Irish taoiseach, or prime minister] Bertie Ahern would be a good EU commission president (he said yes, I said no). We reached a large fountain that sent a cool spray of water out from the rockface that is the side of the headland onto the narrow path. A few groups of tourists had stopped to admire it. There was a young couple there with a child of about one year in a stroller. The man wore a Glasgow Rangers football shirt. I bristle at the sight of it. Who is this guy over here, among these Italians with their Lacoste sweaters draped over their shoulders and these French with their Monaco and Toulouse football shirts? Perhaps this Scot is anxious to show that he is not English (or Irish, God forbid) by wearing this shirt, like a Canadian backpacker with a patch of the maple leaf flag, for the benefit of the rest of us, who think they’re all Americans.

At the top of the fountain was another balcony and people stood up there looking down at us and at the view of the promenade behind us. We walked up the winding path and came to the main attraction at the top of the headland-park. A café had tables outside, but it was too early for us to stop. There was a flat area that offered views to the east and south. We walked across it and watched the Japanese tourists. Two of the women had sun umbrellas open. It is easy to stare at Japanese tourists because they never stare back. It’s almost impossible to make eye contact with a Japanese tourist. Do they secretly watch natives when they are in foreign countries? Maybe from their buses. Maybe through their cameras.

There was a mentally handicapped child up there too, running around happily. It was attended by what seemed to be its grandparents, who looked Italian. The child didn’t look Italian. There was a tall Scots Pine whose upper branches were level with us up on this height and beyond it the blue of the sea. I said to Tom, “Imagine how awful it must be to have a handicapped kid.” The comment kind of caught him off guard, and he didn’t say anything.

I watched the sea and the Japanese a bit more and then realised Tom had drifted off. These moments of separation are as integral to a walk as the companionship itself. They offer a glimpse into the fantasy that one could be here alone, or into the instantaneous daydream of not finding him until hours later back at the apartment (this was spiced up by the realization that I did not have my mobile phone with me). I had no idea which direction he had gone in. I had three options: go and look for him, simply follow my nose and see if I come across him, or stay put and wait till he comes back. The last option was ruled out immediately. It is not something Tom would do and he would not expect such passivity of me. Besides, I had had an eyeful.

So I ambled a little, my pride somehow telling me not to go looking for him, yet a corner of my mind worrying that I might actually lose him. There was another little raised area, offering yet another view of the promenade. I took the steps up and there were two tourist shops beside an ornamental compass and, as everywhere, a little balustrade/balcony lined by people looking at Nice. Tom was among them. I didn’t recognize him at first, and I saw him as a stranger might for a second or two. He and I have not lived in the same place for over five years and I could see those years in him. I came over to him and realized this was the balustrade that was above the fountain. I looked for the Rangers supporter, but he had gone. I bought a metal tray with an image of Nice on it, which I carried around with me in a thin plastic shopping bag for the rest of the day. The picture of Nice on the tray was taken from a vantage point very close to where we were at that moment. Having this picture, I saw no need to take another with the camera.

We walked east across the top of the headland. We passed some shrubs and trees, which I photographed, intending to send them to one of my brothers, whose pastime is to identify plants. I still have not sent them to him, a whole year later. Did I mention I am writing this a year after the fact? Well, no matter. The first plant, a viburnum, had a little sign giving its name.

Reaching the eastern side of the flattish top of the headland, we saw the sea again. A boat in the water seemed to wander, lonely as a cloud. At least, that’s the way I remember it when I look at it now.

It seems even lonelier because the big pixels show that I had to use the digital zoom to get it in any detail. Next was a cactus, the pictures also taken for botanical research.

There is a playground, thronged with children, next to this little tree.

Actually, there were people all around us that day, it being a Sunday in June, but I took hardly any pictures of them. But they were there, I swear. And the next picture is proof. The four men are standing at a balcony (what else?), looking alternately at a schematic view of the actual view of the port and its surroundings; in the schematic view, prominent features of the landscape are represented by their outlines and their names given. The reader may note that the man at far right, baseball cap on backwards (!), is Tom. This is definitive proof that he was there. The schematic view and the view itself are unphotographed by me, but the perceptive and those of faith will be able to see them clearly in the stance, thoughts and words of these four men.

We watched a Corsican Ferries boat arrive below and then we descended the eastern side of the headland along a road that zig-zagged us down towards the port of Nice. We walked under tall trees that kept us in the shade. This was a lusher, greener area. Water rushed along the storm drains on either side, flowing out of the hoses of a whole row of people who were spending Sunday washing their cars. We passed a petanques club on our right.

I set Tom a pop-psychology test in which the answer the subject gives is supposed to indicate if he/she is psychotic. Strange to say, but I cannot remember whether Tom turned out to be psychotic. In my notes which I jotted down a day or so later, I have written: ‘psychopath test, Tom lost’. Does this mean that he failed to find the answer that makes him a psychopath, or that he is a psychopath?

The reader may be able to judge from this picture, which was taken immediately after the test:

If it is difficult to draw a conclusion from this, then perhaps the next picture can help.

What is going on in these pictures is in fact yet another conceptual map of Nice. What happened was, Tom was so engrossed in the psychometric test that he lost track of where we were. These pictures show the confusion and, let’s face it, annoyance that he experienced as he tried to figure out why we had not emerged back onto the city streets where he expected us to. My photographing him probably didn’t help either. He turned his back after a while, but I am not sure if he was trying to ignore the camera or to orientate himself.

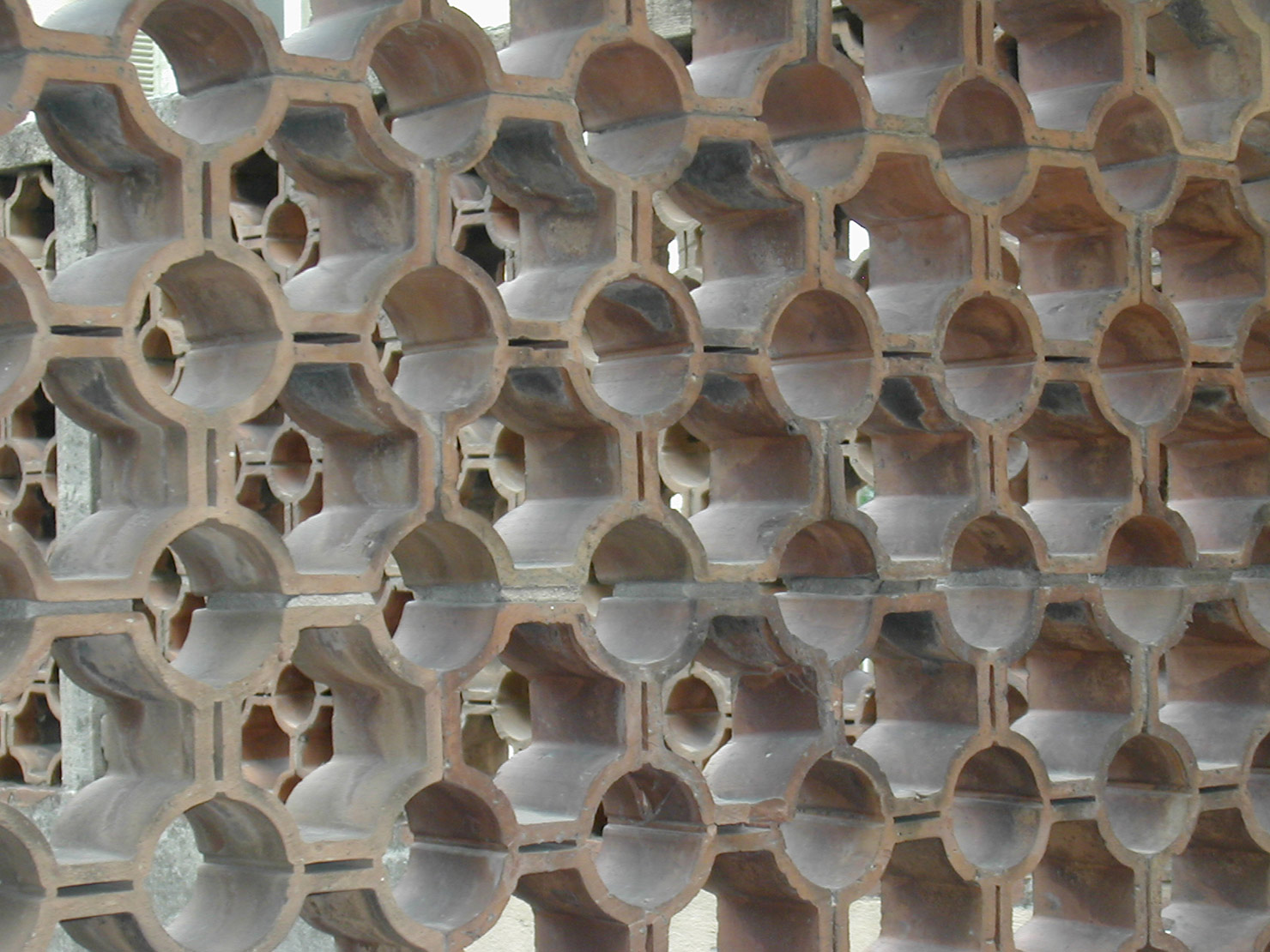

The next picture is of a wall that was on the right hand side of the road just pictured.

And the next one is the view when you look over that wall.

That is my shadow there on the ground and this is the only evidence that I was on this walk at all.

The next couple of pictures are of road sign at the next intersection. The fact that there are a few of them is an indicator of the fact that we stood there for a few minutes while Tom still tried to work out where we were. It is details such as this that we have to rely on to get an idea of the speed at which this route was walked. I am afraid I did not note the times. But take it from me, it took quite a while.

The reason I included the bashed up Citroen is because it reflects one of the themes that Tom kept returning to throughout the walk: how poorly the French economy is doing and how little money there is in France. One symptom of this, in his view, is the poor state of repair of many cars. True enough, once he pointed this out, I noticed that a lot of the cars have dents and scratches that have not been seen to. What this actually means is beyond me. For the moment, let this old Citroen stand for the ramshackle state of France. More evidence.

Also at this intersection, there was a young man on a balcony about four floors up. He was having a heated conversation which we could hear every word of. The whole street could hear him, in fact, but there were very few people about. When you are on a balcony, are you in a private space or a public space? He caught me staring at him. The windows of the apartment he was in had signs saying ‘A VENDRE’ or ‘A LOUER’.

We headed down a street of antique shops, all closed on a Sunday. The area was a little run down. We were nearer the port. We went into the courtyard of a building that Tom said he had almost rented an apartment in.

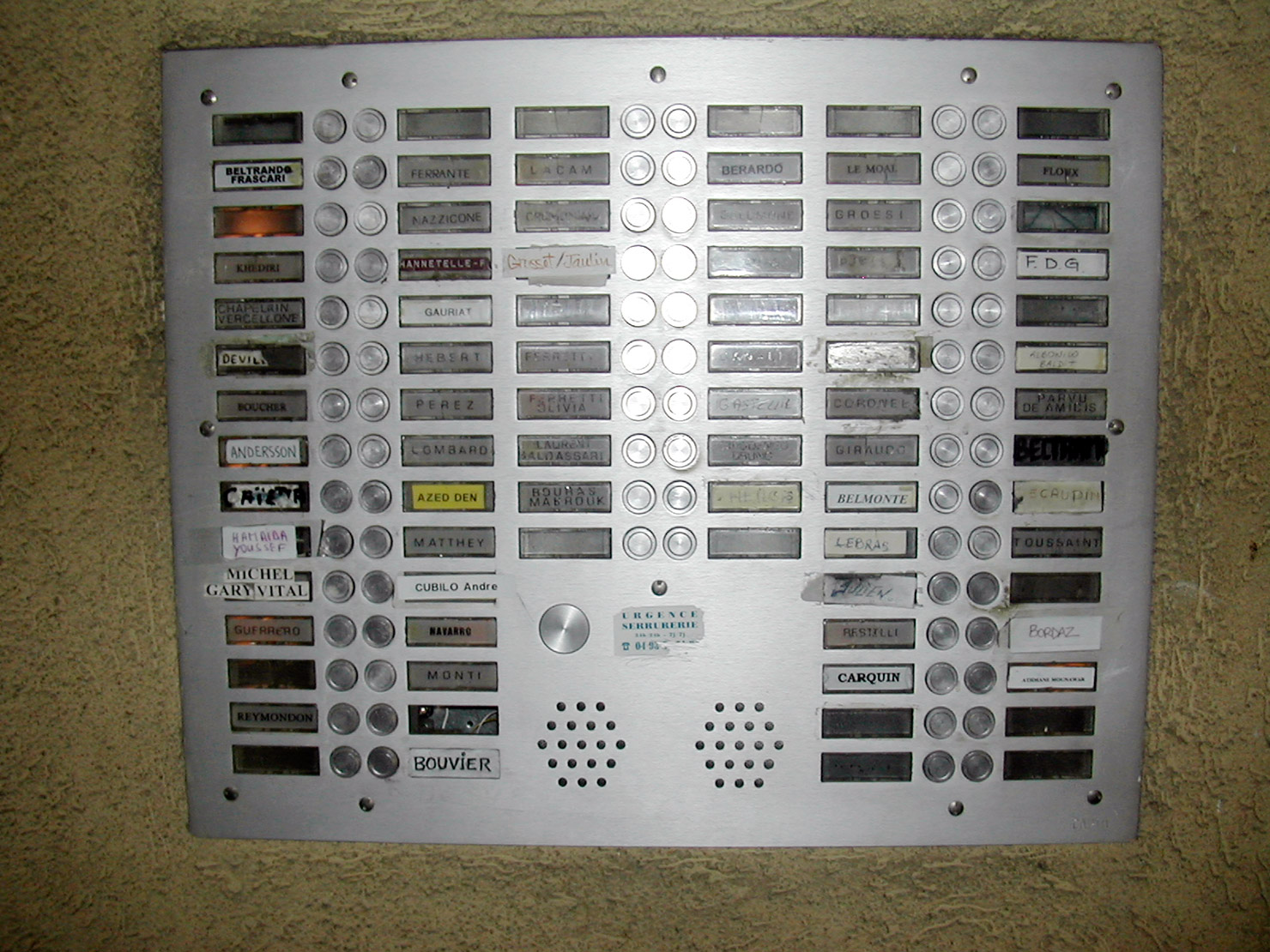

Strange to think that if he had taken a place here that our walk would have been so different. There is an arbitrariness to all of this that makes me think of the Dadaists again. It is absurd to make a record of something as banal as a walk, absurd to mark it out as an event of significance. But what does merit being recalled to memory? The day before, we had made a real walk, a proper walk, up out of the city into the mountains, arriving into hilltop villages and walking among fruit-laden plum trees. Tom had a map, a proper bag, walking boots, packed lunch. There was a plan, a route, ambition. That walk was one that was worth memorizing because it was an occasion, because it would be a good idea to remember it so that you could do it again with someone else or maybe work out a variation on the route. But the tenor of the mountain walk dictated the present one, because we were consciously not having a big walk this day. This was just a stroll and we had no idea where we were going. At least I didn’t. Next are the doorbells that might have featured Tom’s name.

We arrived at the port, looking at some restaurants that we thought we might come back to. There was a Boulevard de Stalingrad, armed police, a rue des Moules or Moulins or something. It all felt very foreign. We followed the road that rings around the inlet that is the port and it led us further east along the coast. Tom says this used to be the main road along this coast and I had been thinking the very same thing. When was it that they built the huge motorway a few miles inland, balancing it on stilts and punching holes in the sides of mountains? The previous day we had looked down from the mountains towards the sea and one of the best things about the view was the sweep of the motorway which in fact ruined the view of the coastline and the sea.

Did people object back then to the new road? Everything in this region is squeezed into the narrow strip of land at the feet of the mountains as they fall into the sea. There was nowhere else to build it. The railway still has some of the best views, hugging the coast at many points, reminding me of the railway from Dublin to Bray.

The path we walked along was less crowded than the Promenade des Anglais, but there were still plenty of people about. To our right below us, on the rocks, an old man in a hat held a fishing rod. Some people were swimming. There were little groups of people dotted around the rocks, sunning themselves, eating from hampers, playing outsized French playing cards which had elaborate illustrations of batons and torches even on the low-value cards. There was a tall concrete diving platform protruding from the terrace of one of the only buildings to be seen along the water’s edge here. The road turned and climbed inland, away from the coast. We moved down onto the rocks, still walking east. The way was not marked, but there was a route among the rocks that everyone used. Above us on our left were large individual houses, villas I suppose, all with large windows fronting onto the water. Some were on stilts. South County Dublin again.

Finally we moved off the rocks and took a steep narrow stone staircase on the left. It led us between the gardens of these villas, which we peeked into from time to time. It was a long climb. A couple of hundred steps at least. Eventually we came out onto a little cul-de-sac. We came round the back of a pizza restaurant and emerged onto the main road again. We crossed it and kept ascending. There was a fenced-off area on our right, about to become a building site. Above us and to the left there was an apartment building. A man stood on a balcony, watching us intently. Tom didn’t notice him and I pretended not to. There was something hostile in his stare.

Abruptly, we turn to the right. Tom is in control of this walk. I am slowly realizing that he knows where we are going, but he is not telling me. He takes pleasure not only in being the guide, the one who knows the way, but also in keeping this information to himself. We walk along a residential lane of high walls with doorways into large gardens and houses. We are following the contour of the mountainside, which is so steep that the roofs of the houses on our right are below us. There is no-one around. The locals seem to like walking only in the city and the parks and along the sea. More sets of stone steps lead off to the left, but they remain paths not taken. Up ahead, there is a road sign with the word ‘NICE’ crossed through by a diagonal red line, marking the municipal boundary. I am looking forward to passing it, to experiencing the moment of leaving the city limits, having set out from the centre just a couple (few?) hours before. But suddenly Tom takes a set of steps to the left and we’re on the up again, still in Nice. For a moment I consider insisting on crossing the line, but some things just have to be let go.

We emerge onto a rough track, which in turn disappears, but we are still climbing. Above us are some trees. In my notes, I have written ‘carob trees without pods’, but I think they were probably the trees that produce St. John’s Bread – those long weird green pods that can be eaten. Maybe that is a carob tree? Two days before, I had taken some pictures of a spectacular specimen next to the wooden hut where Le Corbusier used to holiday, just up the coast from where we are.

A whitish pigeon was ambling along the ground. Tom notices it and asks, ‘What kind of bird is that?’ I laugh and say it’s a pigeon in a mocking tone. Tom says nothing and I feel a bit bad.

Then we reach the next ridge and we emerge onto a newly-laid, perfectly smooth tarmac pathway. It is slightly red and quite soft, like a running track. We turn right, still going east, and then, as if from nowhere, the path is crowded with old people walking in pairs and sitting on benches. They are all old, without exception. It is a little strange. Not true, there was one person there who was not old. I remember because I could not distinguish if it was a man or a woman. He/she was reading a book, sitting on a bench which offered a wide vista of the Mediterranean.

The strange path ends and leaves us onto a quiet road among trees, in a parkland. A few steps further on and we reach yet another viewing point. We have reached the edge of the next headland and the ground drops away below us towards the water. The edge of the land sweeps dramatically inland at this point. To be more accurate: there is a deep bay and we are at the headland where the bay begins.

Tom gets a phone call from a friend in Dublin who wants some advice about buying a house. The phone call goes on for quite a while, so I take out the camera again. As can be seen, I took quite a number of pictures.

I started playing with the camera’s extra-close-up focus function. The first of these pictures shows an ant.

The picture above is another lonely boat shot.

The picture below is an action shot.

This last photo is crucial in the writing of this entire account. As we were looking at these pictures on the computer afterwards, I found myself explaining to Tom what this one is of. And it was then that I realized how many ways there are to offer an account of what we did that day, and that led me on to thinking about the Dadaists, and so on to where I am now. The picture is of the road that passed by us while Tom was on the phone. Every now and then a vehicle would go by. On this winding mountain road, I could hear them approaching before I could see them. I was trying to take an action shot for a change. But I still had not got the hang of the strange delay that there is when taking photos with a digital camera. The instantaneous click of an SLR camera is lacking and I often find digital photos unsatisfactory because they show what has been photographed a second or two after the moment when I wanted it to be taken. They allow you to photograph only what you are about to see, not the thing itself. The camera is already a problematic mediator between us and reality, and especially in relation to how it distorts and controls time. But the digital delay adds a further layer of estrangement. It’s almost like someone else took the picture. The moment that is actually portrayed was spent by me in a moment of silent annoyance as the camera froze the image in preparation for the actual click. Maybe faster processing speed will make all of this sound both redundant and dated very soon. Anyway, the picture is in fact of a French teenager whizzing by on his moped.

The phone call over, we turn north and start heading inland, along the top of the headland. The light is beginning to fade and we are under tall trees, so the circumstances for taking photographs are not good. Still, I stop and take these pictures of flowers. These have also never been seen by my brother, for whom they were taken.

But Tom is keen to keep moving and is not very happy about me stopping. So we walk along at a brisk enough pace. Eventually he releases the information that he is anxious to get a certain bus that might not run after a certain hour on a Sunday. We reach a small piazza, where there is a water fountain that we drink from and a bus stop, but no bus.

I take a picture of this sign, which is familiar to me after years of asking ‘Où est l’auberge de jeunesse, s’il vous plaît?’ in French class.

We have missed the bus, so we press on, heading for another bus stop where we might be luckier. It’s getting darker and we walk quickly on the road under the blackening trees. The park that we are going through is almost empty. The bins beside the picnic tables are full to overflowing, but there is almost nobody there anymore. Tom says the place is called Mont Alban, and I talk about my French friend Alban, who is about to open a bar in Berlin.

The trees thin out a little and there is a long stretch of road ahead, at the end of which is a prominent building, a fortress of some kind. There are recesses in the vegetation on our left where people are sitting in parked cars. I glance at one as we pass. There is a man by himself, carefully dressed, with the door open, music playing. He gives me the eye. I walk on, wondering if Tom realizes we are walking through a cruising spot for gays. As we pass another, he says, ‘It’s so weird, the way they sit there in their cars. It was the same last time I was up here.’ I tell him the awful truth and he ups his speed by quite a bit and I wish he wouldn’t. We reach the end of the cruisers. The fort is large and intact, but there is no time to linger. A bus has to be caught. There is a large modern sculpture that we also have to skip. We are still heading north, inland. There are houses again and more signs of life. We descend a long gradual staircase and after a while onto a small road. There is a house with a large empty terrace that I look at. A dog suddenly barks at us from behind the gate and, eerily, a male voice seems to come from the empty terrace: “Tais-toi!”

We reach a main road and we find another bus stop. Tom lets me know what he thinks of the bus service, which is not good (neither what he thinks, nor the service).

From my notes: “I misbehave slightly by taking some photos of signs while bus is coming.”

We board the bus, where I took the last two pictures of the day. There is a young backpacker near us. We reach the port in surprisingly quick time. I am feeling disorientated at how quickly we are moving past points that it has taken us hours to traverse. A drunk gets on at the square at the port. Tom says all the drunks lounging around at the bus stop are a summer phenomenon. The bus leaves us at the large park in the centre of town that was once the bed of the now underground river. We have a 15-minute walk through town to the house, the fatigue setting in. The streets are empty, some windows of apartments that we pass are lit.

We get back to rue Rossini, where it all started. I am still carrying the metal tray in the plastic bag, which I have been idly winding and unwinding as it hangs from my hand all day. It is a relief to put it down. Tom cooks little red-skinned fish called rouget that we had got at the market on Saturday and which he had left marinating all day while we were out working up an appetite.