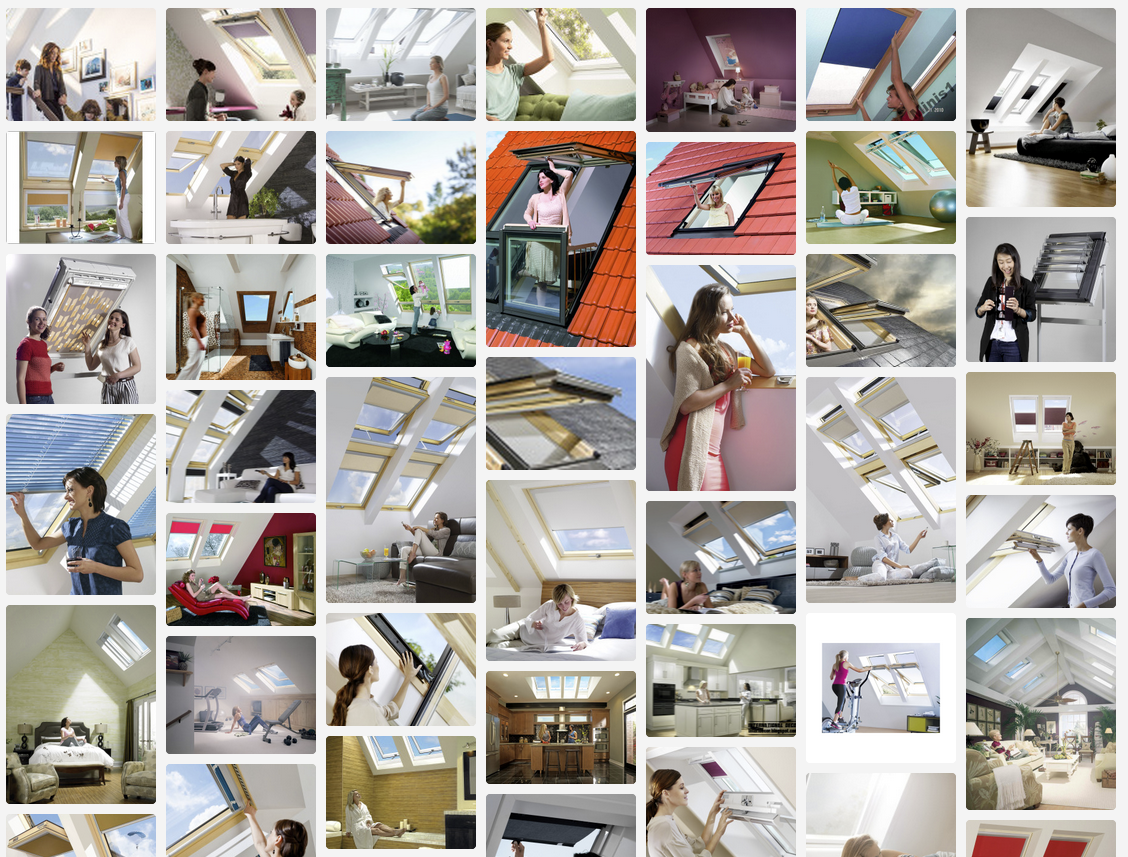

Ladies with Skylight Windows

Recently, whilst researching building materials for an upcoming commission, my colleague mentioned something curious: that there was a discrete aesthetic inherent to the visualisation of skylight windows.

An extensive, multi-language image-search turned up the goods. I did what any other self-respecting blurbanist does, and made a Tumblr for it.

At a guess, 98% of the images featured a female protagonist. The remaining 2% (which I discarded) included various combinations of women depicted within the nuclear family unit, or lone men shown installing the windows. The women in these images appear inside the home, although one or two show woman on the threshold, caught somewhere between interior and exterior. Mostly we see bedrooms, but home-offices, kitchens, bathrooms, stairwells, and even laundry rooms are the spaces which seem to benefit from natural overhead light. Occasionally the skylight-ladies are tasked with some menial domestic task, but mostly they are captured at leisure: some cook with a friend, some lie around reading, some tend to pets or children, some meditated or do yoga. But the vast majority stand at the window and yearn. The yearn is interesting, for it suggests that the skylight window isn’t the sole focus of desire, but the means through which desire is projected outward. Sometimes the yearn is wistful, sometimes intensely introspective, occasionally it is comically euphoric.

The window is presented as a kind of altar, or a looking glass. The light from above represents an ascension – should the window actually be breached – with the woman moving from the confines of domesticity out into the broader world of imagination. The window is a variable membrane, a filter: when closed it becomes an image of the exterior, a promise of something other. When opened, it is a portal fraught with danger: located on the roof, a fall must surely follow an attempt at escape.

The interior is no less fraught with danger, for the images exclude any other means of entry or exit. In one, a banister hints at an adjoining stairwell; in another, a doorframe in the background is obscured by a large plant. The female figure is trapped within the confines of an imagined room, and the camera frame ambiguously defines its extent as a superposition between the fiction of an unbroken spatial continuum, and the strict limits of the picture plane.

The images are uncanny for their inadvertent recreation of an archetype from the Victorian novel. D. H. Lawrence’s The Rainbow frequently portrayed women standing at windows, gazing outward towards the horizon, and forward through time and down the generations where personal fulfillment might be eventually lie. But the images also recall Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s 1979 feminist reading of the Victorian novel, The Madwoman in the Attic, which takes its name from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, in which Bertha Mason is kept locked in the attic by her husband Mr. Rochester.

The perpetuation of such images by the marketers of roof-windows indicates that some societal tropes can be passed down from one generation to the next, pretty much unamended, like a dormant virus waiting for a new host. Either that, or window manufacturers have recently started hiring literary scholars.

Ladies with Skylight Windows

→ ladieswithskylightwindows.tumblr.com